REMEMBRANCES

Robert Carl

I’ve heard that James Sellars died (peacefully I’m told) on Saturday. He’d withdrawn from the world over the past few years, and had suffered from increasing disability, so while a blow, the news was not a total shock. But that doesn’t decrease how incredibly important he was to me and my artistic life (as for so many others). He was a hilarious, challenging, life-loving, sometimes outrageous soul who loved both the conceptual and the sensual in art. His home was a salon for whole Northeast for a couple of decades. I met him at just the right time, and treasured his friendship and counsel. His music really deserves re-viewing; pieces like Haplomatics and August Week are indefinable masterpieces, and I hope will find a way to reach the ears who need to hear them. RIP James.

Juanita Rockwell

Josepine Face Remembers James Sellars (1940-2017)

I recently learned that James Sellars died this past February. James was an incomparable composer, thinker and force of nature and I can’t quite imagine that he’s gone. James used to call me Josepine (which he pronounced “who’s-a-peen”) Facehead, for reasons of his own. I think he meant it affectionately, but who knows.

When I heard the news, I was sitting in a bar in Salzburg with composer Douglas Knehans, discussing plans for our second opera. We’d just seen Alban Berg’s Wozzeck, directed by the South African artist William Kentridge, and were deep in discussion. James came up in conversation and I was thinking that I really wanted to reconnect with him again. I wanted to find out how he was doing, what he was working on, talk with him about Wozzeck, ask him what he was listening to these days. We hadn’t spoken face to face since we’d worked together in Hartford, almost 25 years ago. I had no idea he’d been ill – he’d seemed equal parts monumental and fragile to me, even in those days.

I probably wouldn’t have been in that bar in Salzburg if I hadn’t had the great privilege of knowing James – as well as laughing, eating, arguing and working with him. This was in the early 1990s, when I was Artistic Director of Hartford’s Company One Theater, and I spent as much time as I could in the legendary Hog River Family living room (and dining room, when I was especially lucky). So I must also say that Gary Knoble, Robert Black, and Finn Byrhard – as well as the whole brilliant Hog River Gestalt that vibrated around them – were part and parcel of this education for me.

Another Sellars, the director Peter (no relation, as I recall), preceded James as my first opera mentor. I saw every production of his that I could, and then got to observe the rehearsal and production process of his Marriage of Figaro in the late eighties. So one of the great delights of my professional life was directing James’ monodrama Chanson Dada in São Paulo, BR, knowing that Peter had directed its premiere at the Monadnock Festival. Douglas and I are preparing for the premiere of a monodrama of our own, Backwards from Winter, so James had come to mind more than once during the process of writing it, but I never followed through on my impulse to get in touch with him.

The real crucible of my opera education with James was writing my first libretto (adapted from Gertrude Stein) for his opera The World is Round, then directing the production for Company One in 1993 at The Wadsworth Atheneum, in the same theatre where Stein and Virgil Thompson premiered their Four Saints in Three Acts, 60 years earlier. The two other opera libretti I’ve written since, and the new one I’m beginning now, along with the dozens of lyrics for various plays with songs, have all been influenced by that experience, in one way or another. The World is Round was the first full length work of any kind that I’d written for the stage since undergraduate school, so that was the project that really started me on the path of thinking of myself as a writer, as well as a director.

One day we were working in his sweet little composing studio at Hog River, crammed as it was with instruments of every stripe, going over structural questions about the libretto and its interaction with the music. I muttered something about wishing I’d really studied music composition, learned more music theory, stuck with piano lessons longer – so I could write music. I remember him saying something like this: “Can you make up a tune and hum it? Can you clap a beat with your hands? Then you can compose music.” At the time, I thought he was being a bit disingenuous, or perhaps just uncharacteristically modest. After all, this is a man who composed in his sleep, spinning tunes out of his dreams, humming away in his bed. But the echoes of that conversation come to mind when I think about my decision to start writing songs for my own plays, starting with Broken and Little Patch of Ground.

I don’t call myself a composer. But I am today accorded the great joy of making up tunes and clapping out beats as I work on writing the songs for Splitting Atoms with a Butter Knife, my new play with songs about the Atomic Bomb. Immersed in that history, I’m thinking about impermanence even more than usual. Our parting had been complicated, as they say, but James and I exchanged friendly letters a few years ago, and I’d always thought that I’d see him again someday, preferably during a second production of our opera.

The Hog River house had a truly extraordinary collection of flora, thanks to the brilliant green thumb of James’ partner Gary. There was one particularly spectacular plant, I think it was a Night-Blooming Cereus, that only blooms one night a year. So for one night each year, the giant yet delicate alien blooms emerge for a few hours, smelling like sex in heaven, giving the household an excellent reason for cocktails, company and celebration. I have one of these beauties next to my meditation cushion, although it’s a puny thing compared to the magnificent one at Hog River. It didn’t bloom this year, but I’m going to try to coax a blossom or two from it next year.

Michael Gillette

The late, great, James Sellars--teacher, mentor, friend. It is from him I learned not only about music, but how to listen, how to taste, how to converse, and how to enquire. He challenged me to face the dissonance in my music and my life. In many ways, I am who I am today by sheer force of his will. I would not trade a day and would gladly bargain for more.

Time will say nothing but I told you so,

Time only knows the price we have to pay;

If I could tell you I would let you know.

Kathleen Supove

Thanks for posting, Robert. It brought back a flood of memories. They threw out the mold when they made him! xox and

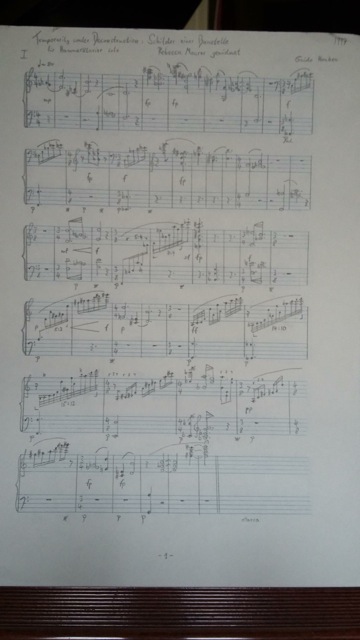

Guido Houben

is with James Sellars.

strange coincidence. yesterday, i was playing thru a piece of mine written 20 years ago that owes much to our great teacher james sellars and that i hadn´t looked at in years, at the hour when he passed away as i learned later that day. rip james.

Istvan Peter B'Racz

Thinking about one of my dear teachers who died yesterday. James Sellars. I had only good memories, and he often took me to task for writing such "ghastly" chords. ;-) ...peace be with you, old friend.

Glen Adsit

I first met James in a rehearsal of his music with the The Contemporary Players Ensemble” in my first year at Hartt the fall of 2000. The ensemble at that point was rehearsing in a room on the 3rd floor that was not really adequate for the ensemble. I walked into the room to James absolutely throwing a fit with the inadequacy of the room and the treatment of the ensemble as the “bastard ensemble from Hartt.” I instantly knew I was really going to like this guy. I very nervously started rehearsal hoping that the same volatility that I witnessed about the rehearsal space would not carry through to his rehearsal. At the end of a very productive and positive rehearsal James came up to me and gave me a big Bear Hug and said "Welcome to Hartt, I am so glad you are here.” What a relief. That was the start of a fantastic musical relationship. James was one of the most well-versed and educated musicians I had the pleasure of learning from. He is missed.

Jennifer Olson

I remember him telling me there were too few beautiful things in this world to discount the importance of a single one of them.

Michael Gillette

The sparkling piano sonatas of the late James Sellars. He is gone now, but his music brings comfort to those who knew him and I hope delight new ears as it has mine these many years.

Scott Metcalfe

Oh no! So many memories -- learned so much from James.

One particular favorite:

JS (pointing to my soprano and string quartet score): "Dear, why did you write these high notes here?!?"

Me: "Uh, the singer asked for more high notes."

JS: "Dear, you don't change notes because a singer asked you to!!!"

[Well, I did end up marrying the singer (Sara)]

RIP and thanks for sharing some of your wisdom with me

Matt Sargent

I'm sorry to hear that James Sellars passed away yesterday. He was a brilliant and difficult person. Sensitive, intense, charming, and defiantly quirky. He held the whole world to a high standard. I feel lucky to have known him.

Gene Gaudette

So sad to hear of the passing of one of my favorite college teachers, the incomparable James Sellars - a gentleman of enormous warmth, wit, and talent. I have vivid memories of Joanne Scattergood performing his "Chanson Dada" at his home in the company of his longtime partner Gary W. Knoble, double bass virtuoso Robert Black, and friends, colleagues, and composition students from Hartt. My condolences to all of his family, especially Gary.

Jost Muxfeldt

James Sellars was a great teacher, dear friend, and source of encouragement and refuge to me over many years. He was also one of the great musical talents I have known in my life, a person who lived and breathed music and art. I miss him dearly.

Jonathan Hays

James's cycle August Week, a setting of a portion of Henry David Thoreau's journals, begins: "August 15th, some birds fly in flocks." I learned the cycle in the summer of 1993 but never performed it. Every year, when I wake up on the morning of August 15th, I sing a bit of the song and think of James.

Guy Protheroe

Very sad to hear this: he was a close friend; I worked with him several times over many years and conducted and recorded a number of his works in the UK and US. A really individual voice. Condolences to his close friends.

Joseph DiPonio

I spent many hours with James Sellars over the course of 2-3 years talking about music, butting heads, and, just as often, simply having a good time. RIP James.

David Friend

Sad to hear about the passing of James Sellars and feeling thankful for the little bit of time I got to spend with him while working on his sublime music. RIP

Thomas Schuttenhelm

The American composer James Sellars died this past week. He lived an exceptional life and created some truly remarkable music. I still remember the first time I met him: it was at a Composers Seminar at the Hartt School and his lecture was one of the most virtuosic performances I ever witnessed. He had such an internal and detailed knowledge of music. He was a master at deconstructing style into its technical components and he would explain and, more importantly, demonstrate, with the flare of a true improviser, how these combined to achieve a desired effect. He was a critical and meticulous composition teacher. Some lessons we barely got beyond two or three measures but I never left discouraged. He held all music to the same high standards and we’re grateful for his uncompromising methods. His own music is a glorious combination of craft and vibrancy, and he left a lasting impression on us all. Rest now James, we’ll miss you.

Gary Knoble to Jost Muxfeldt

His greatest gift to all of us is that he never let us lie to ourselves.

Charlie Scheips

Being with James

I met James Sellars the summer of 1981 when I waited on him in a downtown Hartford restaurant called Fetterhoff’s. As it happened his party was the last table of my lunch shift and James invited me to jump into his navy-blue Volvo station wagon and come back home for cocktails at 1800 Albany Avenue. It was a big summer for me—I had also just met Tom Graf who remains today my best friend and life partner. Now that both our family homes in Hartford are long gone—it is that beautiful house that we consider our Hartford home.

The James I met that day was full of energy, confident, funny and curious about just about everything he could find out about me as our drinks morphed into a delicious dinner in the dining room courtesy of the indefatigable Gary. I was in the process of “coming out” to my parents that summer—and I should say that James, along with Gary and Robert, probably helped me more than all others in guiding me to garner my courage and find my self-worth—that is a longer story to be told at another time and place.

Within months, Tom and I had moved just down the way in to an apartment on South Whitney Street. I landed a boring, well-paying job at Aetna as Tom continued his undergraduate study. We didn’t have a car, so Gary and Bob Harberts drove me to and from work five days a week in Gary’s baby blue VW Beetle. On countless occasions, I didn’t return home after work—but came along for more drinks and dinner at 1800 Albany.

As our friendship blossomed, James would love to share his love of music, both his and others, with me. I remember many an evening sitting on the floor of the living room with James acting as DJ putting LP recordings on the turntable. One of his favorite pieces was the male duet from Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers which he played repeatedly saying, with emphatic joy: “doesn’t it break your heart.” That was so James!

Of the myriad parties and dinners, we had in those early days, the weekend when Virgil Thomson came to stay was one of the most memorable. Virgil asked Gary if any attractive men were coming to dinner—Gary said he thought so. “Then I’ll where a cute shirt,” Virgil croaked. It was, as I remember, a linen shirt with baby elephants covering it. The group photo we all posed with Virgil in the center is now a classic document of that era at 1800 Albany.

Another hilarious weekend was when 1800 Albany hosted gay rights icon and raconteur Quentin Crisp. I remember one morning at breakfast the lavender- haired Crisp announced in front of James: “I have never had a taste for music of any kind.” There were always interesting people floating in and out of 1800 Albany. That house remains today a magnet for talent of all kinds not to mention all the good friends that left us during the height of the AIDS epidemic. Their spirits always remained in James’s conversation and memory long after they had gone.

As I was an aspiring artist, James asked me to make the props for the premiere performance of his 1982 For Love of the Double Bass that he wrote for Robert. I did all but one prop as the dress for the double bass was sewn by none other than Gary’s mother. Over the years, the house acquired several of my paintings and drawings. They span some thirty years of work and include a large collage painting I made after happily shredding my childhood copy of Czerny’s School of Velocity piano practice excercises. For many years, it hung above James’s piano in his upstairs studio.

In time, Tom and I moved to Chicago, and then to Los Angeles. We never lost touch as both of us in those days came back to Hartford for the holidays. That usually meant three: Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Years’ dinners—the first two with our parents—and the final, and always the most fun, at 1800 Albany. In 1991, we moved back to New York and we saw James, Gary, Robert and then Finn, on a regular basis both in Hartford and in New York where they had bought an apartment.

I don’t want to namedrop all the famous names I met in conjunction with my friendship with James, but Leonard Bernstein is worth mentioning. When I ran into Bernstein at a party after he led the LA Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, he started talking to me with his hand on my shoulder while holding a cigarette and a scotch in the other. When I reminded him of our mutual friend James Sellars in Hartford he promptly moved his hand from my shoulder to my rear end!

After Bernstein’s death in 1990, the family allowed us to use the maestro’s legendary apartment in the Dakota for a fundraising cocktail party for James’s premiere production of his opera The World is Round. When I recall that time it must have been one of the prime eras of James’ creative life. Soon afterwards, he asked me to help him produce his fantasy for narrator and electronic music entitled Haplomatics. CD’s had recently become a reality of the recording business and we envisioned a jewel box set containing the CD of the music accompanied by a book illustrating the text and music by David Hockney. One of my great regrets, is that although Hockney created most of the designs for the book it, alas, never came to pass. Perhaps it will someday—it was a wonderful project.

During James’s declining years we still saw him often. Most of his irascibility gradually faded away. But he could be counted on for a good zinger or two occasionally. I remember a large formal dinner that included my father and an old childhood friend. James spent most of the evening with his head on the table as people bantered with each other while eating the several fabulous courses Gary had prepared and drinking delicious vintage wines. Suddenly, James rose up and yelled “your stupid” to my father and “you talk too loud” to my friend. It was all over as soon as it had happened and in fact even before the end of the night we were all giggling about it. James could be a “Drama Queen.”

As James’s illness took its toll, there were still frequent dinners—usually in the kitchen. In his last years, James was always so sweet to me. His face would beam as I walked through the kitchen door with Tom—usually met by a drawling “CHARLIE DARLING” from a grinning James. As the evening went on, James would rest his head as if sleeping but if any of us were speaking about something he was interested in he would suddenly sit up and say something brilliant—or funny—or both! He’d been listening all the time.

He wrote two pieces dedicated to me—the tender Liliaceae (Waltz for Charlie) for piano in TCK Date and a light hearted “A Tune for Charlie” a recording of which featuring he and Finn singing that was sent on cassette tape along with an autographed copy of the manuscript.

For almost four decades I had the privilege to know and love James—and I know he loved me too. Now that he is no longer with us—how comforting it is to still have all his music where his indomitable spirit and amazing intellect still abounds.

I was always glad to be in the same room with James Sellars—and he is always with me. So, it’s fitting I end with the simple lyric line from James’s beloved The Pearl Fishers.

Oh oui, jurons de rester amis!

Oh yes, let us swear to remain friends!

Oh, yes James, we will always remain friends—forever.

David Dramm

Great composer who really turned my thinking inside out as a student in New Haven...

Kyle Phillips

I took this picture of James in 2013.

I would stop by to visit now and then. It was nice to walk up to the house from the driveway and see James inside at the kitchen table reading the Times and sipping a diet Sprite. Often there would already be company in the kitchen but if James were alone I knew I would have some moments with him. Stories, grumblings about what was in that paper, or witty comments but everything came with a smile. James would say to me or those who I brought along, "Darling(s), you are beautiful!" He meant it and it was special each time.

Love you very much James. Darling, you are beautiful. You bright burning, smiling star.

-Kyle

John McDonough

When I was told that James was dead I was gobsmacked. The Arkansan. The James Edward (or Jim-Ed, or Buddy) of Fort Smith. The One who always knew, the One whose opinion mattered -- was gone. And now, the heavy change.

“There is no music now in all Arkansas.”

I wanted to meet the people that had moved into my Uncle Ed’s house in Hartford. That Lulu of a house that my Grandfather’s brother built. From its cedar spiked top floor to its no-nonsense basement of coal and oil, it swirls with the conversations of bygone aunts and uncles. The tearful decision of the twins to become Sisters of Mercy, the gentle, rhythmic sound of Uncle Henry with his bad leg, the still-settling smoke of E.J.’s cigars.

Now James, Gary, Robert, and then Finn move in with a new set of rules. With singing, dancing, treats and music... with the noise of fiddles at our heels, the house changes, and is dear to me.

And yet, “There is no music now in all Arkansas.”

James at the piano. James curled into the arm of the sofa. James with papers and books spread over half the long kitchen table. James the butterfly bush with a coterie of artists flitting round him in the sunshine. James is always there, face and voice vivid in detail.

“There is no music now in all Arkansas.”*

John McDonough

*(line from “Variations for Two Pianos” by Donald Justice)

Alix Hagan

Goodbye, dear James. I'll forever miss your sweet spirit

David Kidwell

Saddened to learn of the death of James Sellars, one of my composition teachers at the Hartt School of Music. At my first interview at Hartt, James played two notes on the piano and asked me, "Which note is more green?" He was quirky, to be sure, but I'm grateful to him for helping me think about music in unconventional ways.

Laura G. Kane

Oh I didn't know. Enjoyed playing his, "Tango for 2 Cellos," with Jeff. RIP James. My condolences to Gary and his Family.

Kellen Booher

I first met James in the summer of 2011 as I was finishing graduate school, and when Robert and Gary traveled to Brazil for a music festival later that summer, I stayed at the house with James for a few weeks. My primary responsibility was to make sure fruit was out for breakfast, the flowers were watered in Gary's absence, and drinks were served promptly at 6pm... one cachaca, one cognac, both neat and on a small silver serving platter. If I didn't serve them on that platter, I would be summarily turned away to retrieve it, with a Maestro Sellars quip dryly echoing off the kitchen walls: "I may not be the queen of England, but I am the Queen Mother." It is unlikely that anyone should ever again occupy the head of a kitchen table so prominently.

Over the course of that summer, we spent afternoons on the porch watching the lime trees grow, holding ourselves a birthday party where we fell asleep under a magnificent oak tree in the backyard and woke up to a tree trimming crew raining branches and insecticide down on us, and running a tab so high at one local wine store that we simply found another until Gary and Robert returned to placate our creditors.

The highlight of our summer was the 3-day trip we took to Manhattan. I was unsure of how we'd navigate the busy streets or if his energy would hold up on extended walks, but we bought ourselves Amtrak passes and headed off at his insistence, jonesing* for an adventure. An innocent stretch of the truth at the train station made for a surprisingly smooth first leg of the journey: "Mr. Conductor," I purred, as James, without missing a beat, melodramatically tottered like a marionette with 2 broken strings, "this is my dear grandfather and he needs a wheelchair and the best seat on the train". After our ruse worked, James turned to me with his wicked, wonderful boyish grin and said "pretty good, eh?" As we wound our way closer to the city, a transformation occurred - James found a renewed level of physical strength that I would never again see. We walked the streets of the West Village as James let 50 years of memories flood over us both, had cocktails at establishments you could only find if you knew where to look, and walked a stretch of 5th Ave in the face of such swarms of tourists that James started swatting his cane at anyone wearing a fanny pack or holding a camera. I feigned mortification, but he knew I loved it. "Pretty good, eh?" and we'd again laugh at our own private joke. Finally, we visited the Museum of Modern Art and walked for 6 hours visiting every exhibit. Some were met with glowing Sellars praise, and others - a wooden lionhead and a cracked eggshell sitting in a 1950s style frying pan - were dismissed with a snort of incredulity and derision: "Pure horse shit!" he would growl. His hearing was diminished by then so his verdicts invariably came out as bellows that echoed off the marble surroundings, leaving me to sheepishly gesture half-apologies to docents and patrons of art. One bespectacled woman sidled up to us though, and, eager to join the Maestro in the audacity of dissent in a place such as MOMA, proclaimed thoughtfully "Well, he's completely right of course. It is total shit."

That was the essence of James, at least as I knew him: a blazing sharp intellect that suffered no fools, a charisma and a dry wit that could turn the most banal activity into the day's highlight, and an unwavering ability to live true to himself in each moment, often quite loudly. I am better for having known him.

* 'hankering for, on the look out for’

Tony de Mare

I met James through my wonderful teacher and mentor Yvar Mikahshoff, who was one of James’ closest friends and colleagues at the time. This was in the early 80’s during my time studying with Yvar. In one his many impulsive moments, Yvar summoned me overnight to come to Hartford (from Buffalo) to bring him a huge suitcase of needed clothes for the premiere performance of James’ Piano Concerto with the Hartford Symphony. Needless to say, this was a fortuitous occasion in that I got to meet James, Gary and Robert and spend a wonderful weekend with them and their amazingly eclectic group of friends. I felt an immediate kinship with all three on that trip, most especially James. In the many subsequent trips throughout the 80s and 90s, my visits to that big wonderful, welcoming oasis in Hartford known at Chez Sellars, Knoble and Black always became a highlight– meeting composers & performers, exchanging and debating musical ideas and trends, and most especially, the camaraderie. As my kinship grew with James, I told him about a year or two into our friendship that I intuitively felt that we were perhaps ‘closely-knit sisters’ from a past life. He smiled brightly.

Of course those years are filled with anecdotes and memories galore involving James – not just musically, but socially – the marvelous communal dinners, playing “Landslide” together at the house, the heartfelt laughter, and for me personally, his very caring support of my career, which was just beginning. One distinct yet silly memory I have from the early 80s was my first visit to Europe with all of them (and Yvar) --- James announcing to Gary in Paris that he wasn’t “… going to eat a bunch of snails with green snot all over them!” – his directness was always refreshing.

I credit that trip partly with the reason why I connected so strongly with his beautiful piano piece “Nocturne – French Dreams”, which I always loved performing. James’ eclectic style during these years fit perfectly with my own sense of programming … there was so much to be learned from him! Not to mention the equally sweet memory of working with him on “For Love of the Double Bass”, which Robert and I performed.

I will miss you James. I am grateful for the years spending time with you, your generosity, your spirit. You were a guidepost professionally, musically and most importantly, a friend who taught me to always be myself!

Jamie Leo

THE JAMES PUSH

I ended up doing one of those things that happened to many people who spent time with James.

At one of the unimaginably beautiful 1800 Albany Thanksgiving dinners prepared, sometimes weeks in advance, by Gary Knoble, Robert Black, with help from Robert Harberts and others (this one in particular had various small musical ensembles join us for each course; they'd play a piece, then merrily head off to own their families' events) James laughed at one of my endless stories and suddenly roared "We've GOT to get you in front of an audience." Now, I had been in front of audiences I had been the fat ensemble member of a highly physically disciplined experimental theater ensemble, working with many of the finest and most disciplined theater ensembles in the world. Microseconds, micropitches, and plastiques (Grotowski's uncompromisingly demanding performative training techniques) were not new to me. I had read my poems on stage beside Allen Ginsberg, I had even opened with a comedy monologue for the Dead Kennedys punk rock band, which all things considered, went quite poorly!

So of course it wasn't long into the next spring before James had me back in Hartford, invited for a three-week residency to work with some of his music students theatrically, and undertake a recital performance of the German-Argentine composer Mauricio Kagel, and his thrilling beast called 'Presentation'. Soon I was working what felt like round-the-clock with gifted pianist David Perry on a 25-minute duet that surely must have had at least two or three stanzas in the same time signature, before climaxing with a staccato dervish of a "laughter fugue". As tough as James was, and sometimes socially (one morning after a late spring frost glazed all the blooming tulips with ice, he chased down undergrad students on the University of Connecticut campus, catching almost everyone whose path he crossed, grinning gleefully, snarling, "Isn't nature LOVELY?!"

But it was seeing James's other side that moved me so much. Fully aware that I had just made miserable technical mistakes in a run through, James paused, stared at the score, then howled, "YOU ARE BRILLlANT!". He knew very well, as I did, that what I’d struggled through had missed MANY marks – and when I apologized he grew sullen. "You are a dream come true to this composer and his IDEA; that you are living and breathing and sweating this work is exactly what a composer YEARN for.

Through James's sheer will, a week later I took the stage to perform at Hartt, aspiring to the best of my ability – and joyfully laughing, at, with, and toward the Olympian order James envisioned for me, as he did so many of us who had the tremendous good fortune of working with him.

Todd Merrell

James Sellars: A Remembrance. A Celebration.

If anyone ever made an art of teaching, James Sellars did. And if anyone ever wrote a music worthy of study, he did.

Our meeting almost never happened.

I’d been studying music composition and voice at Berklee College of Music, and while I appreciated their fast track entree into the essentials of the craft, well - the larger historical, aesthetic and artistic relevance of music and its sister arts, sciences and humanities was entirely absent. I needed more. More background. More context, and - to write an opera! Now!!!

So, at the ripe age of 21 I called the coolest kid I knew in our junior high school, John Surovy. He was now studying harp and composition at The Hartt School, and must therefore have a view of value in the matter. I asked him who the most brilliant and inspired composition teacher was at the school. Without pause the answer was obvious: James Sellars.

So I called him.

He found the method of contact unorthodox, unsurprisingly, but was intrigued by the premise of the project. Honestly, I think he had no idea what to make of me or my proposal, but he was game, if only to get a load of this audacious young upstart. (“…What the hell is he thinking?…”) So, filled with anxiety and excitement, I recruited the support of my best friend Patrick Jordan, and we made the trek north to Hartford.

It would turn out to be kismet.

The only reason I don’t remember what we had for dinner is that the conversation was even more electric than the meal. Firecrackers of ideas and mutual interests flashed across the table: “Oh, you like Laurie Anderson and William S. Burroughs? Do you know her piece based on the writings of Walter Benjamin?”.

We’d both devoured Douglas R. Hofstadter’s ‘Gödel, Escher, Bach’, and Gary Knoble suggested that if I loved ‘The Place of Dead Roads’ so much, really, I ought to read ‘Mrs. October Was Here’ by Burroughs’ favorite author, Coleman Dowell. That book was the perfect diversion while recuperating from the recent extraction of my four impacted wisdom teeth -

(…Ow… Ooh… Oh!…)

- as was ‘Piano Phase’ by Steve Reich, who’d just become my new favorite composer by way of James’ tossed off demonstration of its ingenious construction on the Yamaha nine foot concert grand piano in the living room…

Many more inspired dinners followed. Introductions to the works of Robert Ashley, “Blue” Gene Tyranny, Maggi Payne and the rest of the Lovely Music crew; the brilliant music and criticism of Virgil Thomson (from whom I gained an enormous love and respect for prosody); the music and teaching of Leonard Bernstein; the writings of Gertrude Stein and Tristan Tzara, and the Dadaists, oh, the Dadaists…

…and the ancient music, beginning with ’Sumer Is Icumen In’, and on to Perotin and Machaut and Tallis -

and ending with the newest and greatest of the (post-) ancients:

Stravinsky. Satie. Ravel. Cage.

Soon singular salons succeeded. Brilliant conversations effervesced with Robert Carl, and dramatist Juanita Rockwell and actor John McDonough, the last of whom taught me the wonders of Laphroiag single malt. Bon mots flashed throughout the room like Chinese New Year rockets. We discussed the challenges of engaging new audiences unfamiliar with the canon and I blurted out, ‘I don’t know Smetana from Aetna’.

Then James and I were collaborating. He wrote an arrangement of my piece, ‘JNNY: A Love Song’ which I performed with Fumiko Miyanoo on keyboards, Jeffrey Krieger on electric cello and Robert Black on double bass. Michael Barrett later performed it many times with The New York Festival of Song. (The honor it was, and still is. The humility and encouragement - it drives me now.)

We kept inspiring each other. James wrote a number of chamber pieces for me to sing (I’ll always be humbled), and it was a delicious challenge. Despite my obvious bias, I think this was among his most inspired work. But then again, we connected.

James and Gary introduced to me the exquisite poets, Jonathan Williams and Tom Meyer. By this time the heady mix was too much to absorb - and sustain - and it was time to take flight…

I moved to Chicago, and wrote a few pieces for some of the peerless artists James and company adored - musicians impossible not to write for: Yvar Mikhashoff, Jan Williams, and Robert Black - some of which was performed, and some relegated to the attic of ideas I’d get to fixing eventually. Or not. (A place that Douglas R. Hofstadter called ‘Tumbolia’, the land of dead hiccups and extinguished light bulbs.) Much happened, and I underwent a change in my musical direction. The internet happened, life happened, and time and space inevitably separated us for a time…

And after much too long we reconnected, and continued to inspire each other. We revisited the idea of the opera I’d once proposed, but this time it mutated into a development of the ‘JNNY’ theme as a musical. Like a number of the projects we’d envisaged, it didn’t materialize into a complete form, and I wish we’d seen these projects through. It’s almost as if there were too many ideas, too much possible in the art of the possible between us. Yet I’m all the richer for it.

James Sellars was nothing short of a master. Of his art and of his craft. Of his teaching, and his learning, always learning…

Only a few years before his death he began studying the computer programming language C, a notoriously unforgiving yet resolutely formal and disciplined, rock solid way of telling your computer just what to do, and how. Just because. Because it was challenging. Because it has a kind of perfect beauty in its peculiar syntax and architecture. James was always up for a challenge. He’d read Derrida and Barthes, and introduced me to their work, and I think that while he didn’t always agree with their postulations, he admired those ideas - for their rigorous beauty and irresistibly logical arguments. James didn’t always agree with you, and often that was just what you needed to see: the other side of the coin - the obscure, the shadow of your knowledge, of your curiosity and abilities…

He taught me so much about voice leading and four part chorale writing. (When it became clear that I and another student could clearly benefit from a strong dose of revisiting said good chorale writing, he took on the challenge and became both the best possible teacher of the course, and the best student in the studio.)

He found an irresistible value in Schenkerian analysis, and in the thornier work of composers like Carter and Stockhausen and Ferneyhough. And while he only occasionally saw eye to eye with their aesthetic and philosophical stances (actually, he did rather like some Carter…), and in many ways was fundamentally opposed to them - he respected their intellectual rigor, dedication, and contribution to the canon, and thought it important - rightly, I think - to know their work, and to pull it apart.

James was as comfortable with difference and disagreement as he was with similarity and concord. He knew familiarity and foreignness in a way that few ever have. A student his whole life, he never stopped sharing what he’d learned, not for one single moment, and not even when you wished he wouldn’t learn you, yet again, tonight.

While he taught me so much about the mechanics, history and context of great music, perhaps his greatest legacy in my life - (except completely shaping who I would become as an artist, and how that is a practice, a way of being and doing) - he taught me two great lessons:

1) Artists are afraid of only two things: they’re afraid of failing, and they’re afraid of succeeding.

And perhaps most importantly:

2) People always do the best they can.

Such simple ideas that are really much, much larger than they appear. And thanks to James I must never forget, “Only connect”, courtesy of E.M. Forster. (Let’s just call it the relentless, unending pursuit of truth, beauty, and the betterment of everything for all, if only for our fellow human beings…)

His stories were unbelievable, and he had a wickedly sharp sense of humor, with a particular fondness for the absurd. Stories so good, and witticisms so funny that they could only be told aloud, to close friends.

Well, I tell you, my friends - James Sellars was more than my teacher and mentor.

He was the greatest composer and artist, and thinker, and student and teacher I have ever known, and am likely ever to know. He was something that we don’t have a name for in our culture.

He was singular, irreplaceable, and invaluable. There was such meticulous care in his work.

Every word chosen, every image selected…

(his collaboration with David Hockney, ‘Haplomatics’, immediately comes to mind - absolutely brilliant, inspired and even deeply moving and utterly charming, despite its inscrutable abstraction…)

Every chord, every fermata, every voicing, every note, every articulation, was thoroughly considered, for its meaning and significance, emotional and intellectual import, appropriateness, political relevance, the aesthetic embraced, and the ability to be played with (relative) ease, practicality, and above all, for the performer’s complete engagement. James Sellars, thank you.

For everything. Your legacy is inestimable, and forever. Your deep friendship is one that will be with me always, and the lessons you taught me have become a part of my DNA. I hope that I can pass it on to your progeny. (And on from your progenitors, Mother Omah, and your great teachers Ludmila Ulehla and David Diamond of The Manhattan School…)

…And after all this, I’ve said nothing of his magnificent opera, ’The World Is Round’. Its premiere was among the greatest moments in my life. Just listen to it - it will change you. For the best. Thank you again, Dear James. (Did I mention that he was generous to a fault…? How does one sum up this big a life…?)